Walter Shelton, from a Hanover County family with links to the American Revolution, struggled to keep his wealth.

(This is a slightly edited version of information excerpted from the PDF about a neighboring house at 2720 East Broad, Richmond, Virginia. More details appear in the PDF.)

February 23, 2025

Walter Shelton tied his horse up that crisp morning in 1813 to a low-hanging branch of a tree on the property on Richmond Hill (later known as Church Hill). He walked around the parcel of land and then came back to his horse. He liked what he saw: he could build the substantial house he was envisioning in the middle of the property and still have plenty of vacant space around him. It was different from his boyhood home, that one deep in Hanover County with only a single dirt road several hundred feet away – but the two-acre square here was big enough, and remote enough, that despite the muddy roads that formed the perimeter of the lot, there was a distinct rural feel to it. He could already imagine the house itself – modeled after the home he had grown up in. Yes, this would do just fine.[1]

In about 1812, Walter Shelton of the Shelton family of Rural Plains, Hanover County, built a large home in what is known today as the 2700 block of East Broad Street in Richmond (Figure 1). The Shelton family had been in the Americas since 1638; Walter himself had been born in the midst of the American Revolution. During the war, his father, John Shelton III, who would eventually attain the rank of colonel, marched with the militia of Patrick Henry to Williamsburg to protest the British governor’s action in removing gunpowder from the town magazine. Walter’s aunt (John III’s sister), Sarah Shelton, was Patrick Henry’s first wife. When Walter built the house on East Broad, his own family consisted of his wife, Nancy and five children, the oldest about 12 years old.

Tantalizing details about the dwelling and the property can be gleaned from several sources as the years went on. In 1865, the Robert Lyne family, who owned the property at that time, was seeking to rent the manor house out, and described it as “containing eight or ten rooms, with a garden containing about half an acre of land, … delightful shade, and front yard.”[2] A week later, they edited the ad a bit, saying the house contained “seven rooms besides the basement,” and the garden contained “nearly an acre of rich ground.” A prospective renter would have “use of kitchen” and a “brick stable with six stalls.”[3] The Lyne family was unable to rent out the house and land amidst the hard realities of Richmond’s post-war civil war economy, and it appears to have become a bit of an albatross. They then tried to sell it, re-packaging the parcel as “admirably suited for a large female school.” They described the house at that time as having eleven rooms “besides closets, &c.” There was also a “well of good water on the premises.” [4] In 1937, neighbor George Gay at 2720 East Broad spoke with Madge Goodrich, who was inventorying old homes in Richmond for the Works Progress Administration (WPA), and noted that the house had had “the hall in the middle and rooms arranged at the sides and painted green.” Unfortunately, exactly what was painted green is difficult to discern in the context. [5] From his comment, Gay, who had moved in next door in 1911, may have been in the house at one time; perhaps he had even considered buying it at one time.

With the sum of information about the house and its outbuildings, it feels as if Shelton had intended to re-create a suburban plantation of the sort author Camille Wells describes was present at the time in the Virginia countryside. She quotes a British visitor observing that rural Virginia dwelling sites looked “like little villages, for having kitchens, dairy houses, barns, stables, store houses, and some of them 2 or three Negro quarters, all separate from each other but near the mansion houses.” Wells noted that, “This appearance of a town wherein a landowner’s house stood surrounded by buildings of subordinate function inevitably hinted that the planter represented a kind of mayor…, and this perception never lost its appeal for colonial Virginians.” [6]

Shelton had made a good investment in buying the land and building his house in 1813. In early 1815, at the close of the War of 1812, real estate in and around Richmond rose dizzyingly in price. “City lots … advanced in price two, three, aye, tenfold,” wrote Samuel Mordecai, the early Richmond historian, and in the suburbs, like Richmond Hill, “instead of being sold by the acre at ten to fifty dollars, [lots] were retailed by the foot at ten to fifty times their former value.” [7] Shelton regularly insured his house against fire through the Mutual Assurance Society. The Society required policyholders to reevaluate their policies every seven years, but Walter Shelton updated his in May 1818 after only five years, insuring the house with no changes to its footprint at $8,000 instead of the $5,000 he had insured it for in 1813.[8]

Walter Shelton’s wife, Nancy, died sometime in or before 1815 which would have been not long after the family had moved into the Square 23 manor. When her father died in 1815, he left Walter, on behalf of Walter and Nancy’s children, 11 of his enslaved people: Daniel, Charlotte, Hannah, Washington, John, George, Polly, Tab, Lucinda, Davie, and Robert.[9] It is likely all of those enslaved people lived on the property at Square 23.

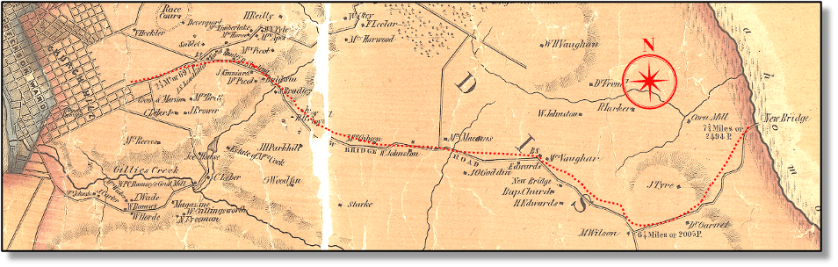

That same year, Walter took out $1,100 of fire insurance on a tobacco factory with an accompanying kitchen he owned on Richmond’s Main Street, perhaps located on the same land he had already owned as early as 1810.[10] His tobacco business must have been at least somewhat successful: an ad in the New York Post listed Shelton’s tobacco for sale.[11] In addition, possibly following in the footsteps of his grandfather, John Shelton II, who owned Hanover (County) Tavern in the mid 1700s, Walter owned Freeman’s Tavern located at the intersection of today’s Nine Mile Road and New Bridge Road in Highland Springs in Henrico County (Figure 2). He had purchased the tavern and the 144 acres it sat on in 1811.[12]

In June 1816, Walter Shelton announced plans at the Eagle Tavern in Richmond to raise capital for building a Chickahominy Turnpike. It would run from the termination of 25th Street, near his home on Richmond Hill, to Freeman’s Tavern (Figure 3).

Regional Turnpikes

In the early 1800s, it took almost a month of rugged travel to transport goods back and forth from the Salt Works in Wythe (now Washington) County to Richmond. Merchants making the trek would hide bags of gold in casks of melted tallow in a large bale of hay in case of robbery. Entrepreneurs turned to the development of turnpikes – the American word for toll roads – to solve these problems of efficiency and safety. The first turnpike in the United States, established sometime after 1722, ran from Warm Springs, Virginia, to Jennings Gap, Virginia, and cost the traveler a penny. [13]

Turnpikes were privately built and very expensive, and so turnpike companies were chartered to fund them. The first turnpike charter in America was also established in Virginia – the Fairfax and Loudoun Turnpike Company of 1795. By 1816, when Shelton began planning his road, hundreds of turnpike companies had been formed in Virginia, and more than 300 turnpikes had been built entirely or in part. There were so many turnpikes leading to Richmond in the early nineteenth century that it was nearly impossible to avoid paying tolls to get to Virginia’s capital.

Despite the need for improved roads, the economics of nineteen century turnpikes were dismal for their builders. Many failed to raise the money needed to begin their roads, or once begun, to complete them. Men who could be persuaded to invest in turnpikes were generally those who believed they could profit in other ways than tolls: they would be able to transport their produce from their otherwise almost inaccessible farms while also bringing home cash and store goods from town, or they would be able to develop their wilderness tracts into house lots and villages.

Brook Turnpike is probably the best remembered turnpike remnant in Richmond today. Chartered just four months before Shelton’s scheme, it was a popular thoroughfare for farmers bound for “Richmond Towne” with farm goods from tobacco to turkeys. In later years it became the favored road for large coaching parties, picnics, moonlight rides, or supper and dancing at the Yellow Tavern located approximately at the site of today’s St. Joseph’s Villa on Highway 1. It was also the main competition for Walter Shelton as he tried to attract investors to his road.

Richmond Hill Turnpike

It took Shelton some time to get legal authorization to establish his turnpike company. It was finally approved by the state legislature on February 2, 1818; by this time, he had had second thoughts about the name and it was now called the Richmond Hill Turnpike Company.[14] Books would be opened for receiving subscriptions at a cost of $15,000 per share, an almost inconceivable amount, at the Union Hotel on February 19 under the direction of “John Adams, Samuel G. Adams, George W. Smith, John Enders, Walter Shelton, and William Selden.” [15] An ad soliciting 10-15 men to work on the road appeared on May 19.[16] Payments of $10 per share were quickly announced on June 2, 1818.[17]

The state legislature not only controlled charters for turnpike building but also regulated construction and established rules for widths or roadbeds, materials used, and the presence of side lanes for passing purposes. Even so, a “Hanoverian” reader complained to the Richmond Commercial Compiler in August that “the method in which the [Richmond Hill Turnpike] road has been commenced is certainly new to me, it being different from any other that I have seen.” He continued, “The two outside roads are too narrow…” He suggested that the company build outlets every mile or two to allow for passing. “

In September, an advertisement soliciting stone masonry bids was placed for a bridge over the creek “commonly called Stoney Run.”[19] A resident near the road sought to capitalize on his location nearby by offering to sell 100 acres “near Mrs. Dabney’s Tavern and the Richmond Hill Turnpike Road.”[20] On December 9, the company announced a dividend of $5 per share.[21] By January, however, the effects of what would become known as the Panic of 1819 began to be felt in Richmond. The first widespread and durable financial crisis in the United States, it was brought about by an abrupt halt in the growth in trade following the War of 1812. Unemployment mounted, banks failed, mortgages were foreclosed, and agricultural prices fell by half. “Richmond was hit hard,” Virginius Dabney wrote in his Richmond: The Story of a City. “The price of tobacco fell” and some of the wealthiest Richmonders “were reduced to a state of extreme embarrassment and distress.” He continued, “Real estate values plummeted. A house that was worth $5,000 in 1818 was worth only $2,500 a year later and $1,250 the year after that. … [Many people] suffered heavy losses or were completely ruined when the bottom dropped out.”[22]

The Richmond Hill Turnpike Company project collapsed. Although there is one mention of the road on December 25, 1819 (Philip Duval was selling land near the turnpike termination near the Chickahominy River), no other mention of the turnpike can be found after that.[23] In August 1819, Walter conveyed the two-acre property on Square 23 along with several other properties to trustees W. B. Chamberlayne and G. H. Bacchus as a guarantee to pay money owed to debtors. The deed showing the sale is very complex and confusing, detailing the several different ways Shelton was raising money owed. In addition to the Square 23 property, there are mentions of unresolved estates and money owed to and by Shelton to and by several different people not seemingly associated with the turnpike partnership. Belongings and property were sold: a wagon, household furniture, Freeman’s Tavern, several plots of land in eastern Henrico County, and an enslaved boy named Jack. Shelton was able to arrange that he would be allowed to stay for a year in house on Square 23 and would presumably be allowed the use of some of the personal items in it: “four bedsteads, beds, bedding & one mahogany side board, one set of mahogany Dining Tables, one Tea Table, one set of table and tea China ware, one mahogany sofa, three dozen Windsor & other chairs, one carpet, set of silver table & tea spoons, silver soup & punch ladles, a quantity of cut glass ware” (see sidebar, “Mahogany and Wealth”). Excluded, however, was a dressing glass (mirror) which had been given to Shelton’s daughter Mary, another bureau which had been given to his daughter Eleanor “several years ago,” two bureaus, one with a mirror, and all other articles of household and kitchen furniture.[24]

In October 1821, Chamberlayne and Bacchus ran an advertisement in the Richmond Enquirer listing Shelton’s properties and belongings up for sale, including:

- The two-acre Square 23 and the house (Shelton was still living there)

- Freeman’s Tavern with 200 acres

- An additional twenty acres near Freeman’s Tavern

- Five acres near Richmond on the main road from Rockett’s to Williamsburg

- Two other lots adjoining the five-acre parcel

- Two lots at Rockett’s Landing

- Walter’s rights to the estate of Alexander B. Shelton, Walter’s deceased half-brother who owned a share of their father’s (John Shelton II of Hanover County) estate

- The following enslaved persons: Tom Jefferson, Tom Sharp, Ben, and Esther “and their increase.”

- Furnishings listed in the August 5, 1891, deed.[25]

Shelton’s mother-in-law, Mary R. Lewis Price, died the next month, which may have allowed Walter to stave off the auction for a short while the family waited to see what Shelton would inherit – which turned out to be nothing (more information about her will is in the PDF). The sale of Shelton’s property, then, was held in early February 1822. Walter’s late wife’s family seemed to come to his rescue, at least to a certain extent, with her uncle, Gilley Lewis (Mary’s brother), purchasing the property on H Street, “a square of lots with houses thereon,” for an inflated price of $4,800.[26] The word “house” in the 19th century had a broader meaning than how it is typically used today and “the houses thereon” would have been a reference not only to the manor house that Shelton had built but as well as, likely, dwellings of enslaved persons, stables, kitchens, or other outbuildings.

Walter Shelton, 44, was effectively broke.

Walter Shelton largely disappeared from press coverage after his turnpike investment debacle. In the late 1820s, he was involved in some kind of lawsuit in Lynchburg, Virginia, but was back in Henrico County – in the eastern district – by the time of the 1830 census, apparently with his son, living not far from names familiar to the story of Square 23: Samuel Garthright and Joshua Goode. He had recovered from his financial losses enough at the time to have six enslaved people living in his household – perhaps a family, based on their ages. Notice of a lawsuit filed against him in 1840 in Richmond mentioned he was no longer in Virginia.[27]

In 1853, his daughter Mary Shelton Ruffin, 48, died, and her obituary noted that she had moved to the Memphis area in about 1833 with her father.[28] Her brother William apparently also moved with them at the same time; by 1849, at least, he was running a drug store in Memphis and did so for many years.[29] Circumstances of his death are unknown.

It is not known why the family moved to Tennessee.

Walter, 75, died in western Tennessee in June 1852.[30]

[1] This account is an imagined scenario of Walter Shelton’s first look at the property he would buy – known then as Square 23 – bounded by today’s Broad and Marshall streets on the northeast and southwest, and 27th and 28th streets on the northwest and southeast.

[2] Classified advertisement, “For Rent,” Richmond Times, December 28, 1865.

[3] Classified advertisement, “For Rent,” Richmond Times, January 8, 1866.

[4] Classified advertisement, “Executor’s Sale” Richmond Dispatch, August 27, 1867.

[5] Madge Goodrich, “Gay Home,” Works Progress Administration of Virginia Historical Inventory, October 22, 1937 (online:) Library of Virginia. The house eventually took on the address of 2712 East Broad. The footprint of the house is shown in the 1867 Michie map (see Figure 8.4 in Part VIII, “Discussion on the Age of the House”) but was gone by at least by 1910 when news articles and advertisements in the local press indicated that the property had been divided into the three lots that exist today with separate apartments in each one.

[6] Camille Wells, Material Witnesses: Domestic Architecture and Plantation Landscapes in Early Virginia (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2018), p. 13.

[7] Samuel Mordecai, Virginia, Especially Richmond, in By-Gone Days; with a Glance at the Present (Philadelphia: King and Baird Printers, 1856), p. 219.

[8] “Walter Shelton,” Assurance Society Policy No. 2520, May 1, 1818, Richmond, Virginia: Special Collections (online), Library of Virginia.

[9] Will of John Price, December 30, 1815 (recorded March 7, 1816), Will Book 5:68, Henrico County, Virginia. Price apparently had more than 43 enslaved people since he also left his plantation to his wife, Mary, along with all other slaves there “not before mentioned” as long as she remained widowed. Per his will, the named enslaved people and their new enslavers were: Isaac, Patrick, and Maria, who went to Price’s son Marrin; Tom, Nelson, Morris, Fanny, Patsy, John, and Milley, who went to Price’s son John, Jr.; Patton, Grace, Judy, Miles, Philona, Davie, and Stephen, who went to Price’s son Francis R.; Randolf, Amy, Patsey, Major, little Sylvia, Moses, Isaac, Ned, and Jacob, who were to go to grandson Wilson Price when he reached the age of 21; Biddy, Tiller, Agnes, Tom (the son of Biddy) and Emmanuel were to be lent to his daughter Susan Carter during her lifetime and after her death be equally divided among her children; a mulatto woman named Delphia was lent to Price’s wife until Mary’s death. At Mary’s death, the plantation and all the enslaved people still with Mary at that time were to be divided among the same heirs. Walter does not appear to have ever remarried.

[10] “Walter Shelton,” Assurance Society Policy No. 1877, December 27, 1815, Richmond, Virginia: Special Collections (online), Library of Virginia.

[11] “Richmond manufactured tobacco,” New York Post, November 6, 1816.

[12] “Elizabeth Allen [and others] to Walter Shelton,” March 19, 1811, Deed Book 10:70, Henrico County, Virginia.

[13] The information in this section borrows heavily from a wonderful four-part series written in 1951 by Ulrich Troubetzkoy for the Richmond Times-Dispatch about turnpikes in Virginia, focusing on Richmond: “He Built Good Roads,” September 9, 1951; “Traffic Overloads on Virginia Roads a 100-Year-Old Problem,” September 23, 1951; “Most ’51 Virginia Highways Follow Old Turnpikes,” September 30, 1951; and “When Virginia Moved West,” November 11, 1951. Troubetzkoy, whose first name was Dorothy (which may surprise the reader), is a fascinating individual herself; and more can be learned about her from her 2003 obituary: https://www.courant.com/obituaries/ulrich-troubetzkoy-hartford-west-hartford-ct/.

[14] “Virginia Legislature,” Richmond Enquirer, February 5, 1818.

[15] Advertisement, “Richmond Hill Turnpike,” Richmond Enquirer, February 19, 1818. This John Adams, of course, is not the one who was president of the United States who rather was from Massachusetts and died in 1810.

[16] “Wanted to Hire,” Virginia Patriot (Richmond), May 19, 1818.

[17] Advertisement, Richmond Commercial Compiler, June 2, 1818.

[18] “Richmond Hill Turnpike,” Richmond Commercial Compiler, August 20, 1818.

[19] Advertisement, Richmond Commercial Compiler, September 29, 1818.

[20] Advertisement, Richmond Commercial Compiler, October 15, 1818.

[21] Advertisement, Richmond Commercial Compiler, December 9, 1818.

[22] Virginius Dabney, Richmond: The Story of a City (Charlottesville:The University Press of Virginia, 1976, revised 1990), p. 103.

[23] Advertisement, Richmond Enquirer, December 25, 1819.

[24] “Walter Shelton to W. B. Chamberlayne and G. H. Bacchus,” August 5, 1891, Deed Book 21:355, Henrico County, Virginia.

[25] “Notice is Hereby Given,” Richmond Enquirer, October 12, 1821.

[26] “[?] Bacchus and Wm B. Chamberlayne, trustees of Walter Shelton, to Gilley M. Lewis,” February 1, 1822, Deed Book 25:21, Henrico County, Virginia.

[27] Lynchburg: e.g., notice, “Virginia,” Virginian (Lynchburg), July 17, 1826. In Henrico County: 1830 U.S. Census, “Walter Shelton,” Eastern District of Henrico County. Lawsuit: Notice, “Virginia,” Whig, May 15, 1840.

[28] “Obituary,” Daily Eagle and Enquirer (Memphis), May 31, 1853.

[29] E.g., “Removal,” Memphis Daily Eagle, February 5, 1849.

[30] “North Meets South – Pat and John Iverson’s Extended Family,” Family Tree, www.ancestry.com, accessed October 28, 2024. The information is otherwise unsourced, but Mary Ruffin’s obituary notice stated he was deceased at the time of her death, so this is plausible.