This is an edited excerpt from the social history of a house located in Union Hill, Richmond, Virginia available here as a PDF. Please contact me here with any questions.

March 24, 2025

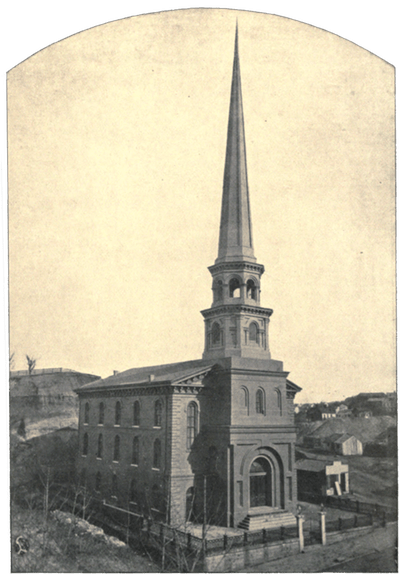

It was a 10-minute walk from his home on Twenty-Third Street to the church. It was a fine fall day in 1873, perfect weather for beginning work on the steeple. It had been a long time coming. Work had started on the church back in ’59, before the war. Obviously, a lot had happened since then. Joseph Newell, 51, reflected on his time in the Confederacy, and how he’d come back to the city to see much of it destroyed by fire. Trinity Methodist had been spared, though, and so had Broad Street Methodist 10 blocks closer into town, even though the latter was located much closer to the burnt district. Broad Street Methodist had been completed by the time the war started. Its steeple stood in testament not only to the fact that it had survived, but it also had the effect of reminding the worshipers at Trinity that they still had work to do. Joseph and his partner William Liggon had worked on the construction of Trinity after the war, but still, completion of the steeple had lagged. It was fitting that he finish the job that they had started. His sons had gone straight to the warehouse to pick up the materials they would need today, and the three of them would work long hours to get a good start on it for all to see.[1]

Trinity Methodist Church and Its Steeple

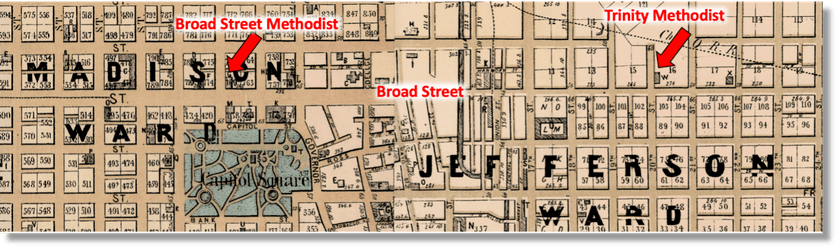

The story of Trinity Methodist and the older, similarly-constructed Broad Street Methodist is sometimes confused in historical accounts because both churches were built in Richmond around the time of the Civil War, both were located on Broad, and both were designed in the popular Italianate style by noted Richmond architect, Albert L. West (Figure 1). The two churches trace their roots to 1790, when the first congregation of Methodists in Richmond organized a Sunday School at the foot of Church Hill. Trinity, at East Broad and 20th Street, is today New Light Baptist Church. Broad Street Methodist – across from the capitol building at East Broad and 10th, part of today’s Virginia Commonwealth University’ Children’s Hospital – was torn down in the 1960s. That two large Methodist churches “could flourish [in the mid- to late-1800s] just 10 blocks apart” (Figure 2), was “indicative of how densely populated pre-electric streetcar Richmond was,” notes a 2014 account of the history of the two congregations.[2]

Broad Street Methodist Church was completed in 1858, three years before the Civil War. The timing of construction was less fortunate for Trinity: trustees of the church did not contract with West for creating the drawings and superintending the construction of the building until December 1859. Some work on the building was done, but with the outbreak of war in April 1861, the bones of the building were hurriedly roofed in, and the basement was readied for worship as an alternative for the planned sanctuary which would have to wait. West, the architect, 34 at the time, joined the Confederate Army and was ordered to Augusta, Georgia, where he remained during the course of the war.[3]

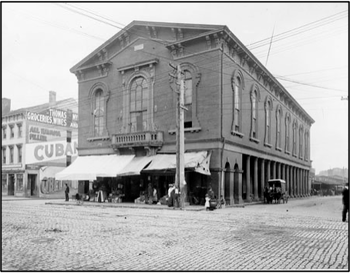

At the close of the war, construction on Trinity Methodist Church was resumed, with Richmonders William Liggon and Joseph Newell as the contractors.[4] Newell, who had been in Richmond since at least February 1848, started his career modestly as a carpenter but had become known as a builder of much bigger projects very quickly, notably the 1854 addition of a second story to the old First Market at Main and 17th streets. A photograph of the building shows that the second story was nothing if not voluminous, with wall heights that appear to be some 20 feet tall (Figure 3). Meant to be utilized as a community meeting hall, it was so striking when completed – the walls and ceilings were frescoed with “beautiful little birds” painted on them – that there was controversy over who should be allowed to use it.[5]

At Trinity Methodist, after the war, additional work was done to the church so that with everything done except for the steeple, it was dedicated into service in September 1866. In 1873, architect West, “ardently desiring to see the consummation of his work,” prepared a revised plan for the steeple and presented it to the church building committee. Once again, the church contracted with Newell to build it. (Newell’s partner William Liggon had died in June 1871, and Newell was in business for himself.[6] The Newells may have been members at Trinity; they were, at the least, Methodists.[7]) Made of wood with an iron finial and a copper point tipped with platina, a silverish-white transition metal, the spire reached a height of some 200 feet above the street curbstone at the corner of the street, about 15 stories high.[8]

The Steeples of Richmond

“Richmond is, more than most cities, a church-going community,” an 1893 guidebook to the city noted,[9] and its churches were without exception mentioned in tourism tracts aimed at visitors to the city in the late 1800s and early 1900s. St. John’s on Broad was the most famous of Richmond’s churches, of course, being the home of Patrick Henry’s stirring revolutionary speech in which he implored, “Give me liberty or give me death!” on March 23, 1775. Church steeples had always been part of the fabric of the city as well. Regardless of whether they had a bell or not, the spires projected their message out and beckoned their parishioners in. By the turn of the 20th century, at least 10 Richmond churches had architecturally important steeples (Figure 4).

The steeples of both Broad Street and Trinity Methodist churches had been designed by West so that they were among the highest in the city and would dominate Broad Street from opposite hillsides above Shockoe Valley (Trinity’s was taller than Broad Street’s, however). In so doing, West “acknowledged the value of the Christian spire in defining neighborhoods and vistas,” according to the nomination form for Trinity’s placement on the National Register of Historic Places. In the case of Trinity, West placed the spire such that not only would it “dominate Broad Street on the east-west axis; it (was) also directly on axis with Hull Street across the James River.” The nomination form adds that “the tall spire and stage tower, and the landmark siting (of Trinity), owe something to John Nash’s 1822-1824 All Soul’s Church, Langham Place, London.”[10]

Madge Goodrich, cataloguing historic buildings in Richmond for the Works Progress Administration (WPA) in 1936, wrote that Trinity was a “gem of architectural beauty and comfort.” She continued, “(the) beautiful tall spire which is wonderfully symmetrical and remarkably well propositioned” could be seen from “a considerable distance in the west, glimmering against the sky.”[11]

Well-known local historian and preservationist Mary Wingfield Scott also thought the spires of the twin churches were significant. She wrote in 1950: “The most striking features (of the two churches) are the rhythmic rows of round-arched windows and the way the spires, placed over the entrance porches, command (each) building.” She had some criticism, however, of the exuberance of West’s design of the steeples: “(In the case of Trinity), one feels a certain amateurishness … that the spire is too high for the small size of the church. This disproportion was probably less marked at Broad Street [Methodist], partly on account of its location on a flat street.”[12]

The Richmond News Leader was untroubled by any supposed imbalances in the architectural design of the steeple, calling it a “graceful needle spire” in 1954.[13]

Built of wood, early steeples were susceptible to insect infestation and rot, and they were expensive and difficult to maintain. Workmen had to climb their way upwards inside of their sometimes very narrow cavities as near as possible to the top, stair-stepping up structural interior beams – which could themselves be unsound – to access a hinged flap that would allow their exit. From there, they would somehow balance themselves to tie a rope to a hopefully-stable exterior tip. The danger in undertaking even simple repair jobs “was appalling,” a reporter noted in 1900, but could also be entertaining to those who watched safely from the ground: “On Wednesday last, a small black mass was noticed away up at the top of the [Broad Street Methodist steeple, at the time the city’s second highest steeple at 209 feet], and speculation as to what it could be was rife. People soon noticed, however, that ropes were dangling from the top, and finally when the creature began to stir on its perch, it was discovered to be a man. He was preparing to paint the steeple.”[14]

The tall steeples with their decaying timbers were particularly vulnerable to wind damage, and Richmond was no stranger to strong winds. In 1896, several churches were damaged and houses unroofed in a violent windstorm that swept over the city. One of the spires of the 6th Mount Zion Baptist Church was torn away, the steeple of the new First Baptist Church of Manchester was destroyed, a portion of the steeple of St. John’s Church was blown off, and a falling spire seriously damaged the (White-congregation) Second Baptist Church.[15]

Trinity sustained no reported damage, and the main structure of Broad Street Methodist Church’s steeple was said to have been largely spared, though the storm winds “carried off” some of the covering boards. By October 1911, however, Richmond’s newly-hired building inspector found Broad Street Methodist Church’s steeple to be in “especially dangerous” condition: supporting beams had slipped out of place, and the “old wood frame affair of antiquated type” was found “utterly worm-eaten and rotten.”[16] Its condition presented a “menace” both to the church and to the neighborhood.[17] Workmen took down the spire three weeks later.

If church steeples were costly to maintain, they were even more expensive to replace, especially after new building codes mandated that no more wooden steeples could be erected in Richmond: they now had to be constructed with a steel frame and faced with a “fireproof hollow tile.”[18] Some of the old, original church foundations were not engineered in such a way as to support the additional weight of this new, required form of construction. Broad Street Methodist elected not to rebuild its spire. In 1950, Scott wrote, “…the steeple that Broad Street now sorely lacks may be replaced in imagination by a glance across the valley to the slope of Church Hill, where one sees the spire of the former Trinity, fortunately thus far spared” (Figure 5).[19]

Demographic Changes and the Beginning of Preservation Efforts

The opening in 1888 of Richmond’s first electrical trolley line accelerated Richmond’s expansion – to the west. Many White families in Union Hill, Church Hill, and other eastern neighborhoods began to move to the segregated neighborhoods of the western suburbs where the houses and yards were bigger and the air and water cleaner, but the men could still take the tram to their jobs in the city and the women could go downtown to Broad to do their shopping. According to Scott, White Methodists who remained in East Richmond attended Church Hill Union Station Church or recently-built churches further east, leaving the old Trinity to be operated as a mission church within a growing community of African American Richmonders. In 1945, the old Trinity building was sold to the Church of God, and the name Trinity itself was carried to the Methodist congregation’s new location at Forest Avenue and Stuart Hall Road, west of the Richmond city limits then as it is now. In 1947, the church building was sold again, this time to New Light Baptist Church, an historic African-American congregation which occupies the building still today.[20]

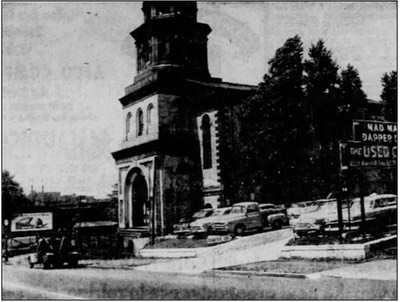

By the mid 1950s, preservationists, inspired by Scott’s work, were beginning to take an interest in buildings which had been suffering from a lack of public interest. Sadly, however, the Richmond Times-Dispatch published a photograph in 1954 which showed that property values were low enough and zoning regulation lax enough that a used car lot had moved in next door to New Light Baptist Church – the former Trinity – considered an indignity to the historic old building (Figure 6).[21]

Only two months later, the steeple built by Joseph Newell on the old Trinity Church – in 1954 the New Light Baptist Church – seemed to be heading toward the same fate as that of Trinity’s old twin Broad Street Methodist Church. Richmond’s building commissioner reported that there were many loose planks on the steeple with openings between them which caused wind to exert dangerous pressures within it. The “graceful spire,” which could be seen as one approached downtown Richmond from many directions, had been preserved in the paintings of many artists and photographers as a landmark of the city, but the building commissioner ruled it must come down.[22]

There was an effort to save it: Richmond resident Natalie Blanton wrote a letter to the editor of the Times-Dispatch in favor of its restoration, “Are there not literally hundreds of church people with enough imagination to make them want to assist the New Light Baptist Congregation” in restoring the spire?” she asked.[23] A committee was formed to fact-find the cost of restore it.[24] The pastor of New Light expressed support for its rehabilitation.[25] Money-raising efforts began. And then, two months later, Hurricane Hazel blew up the Atlantic coast and into Richmond.

Thousands of people were made homeless as Hazel ripped through eight states and Washington, D.C. In Richmond, two people were killed and storm costs were estimated in the millions. A poignant illustration of the storm’s damage was Trinity’s steeple: “For 80 years the graceful needle spire of Trinity Methodist Church had withstood nature’s violence,” the Times-Dispatch reported. “But yesterday it succumbed to Hurricane Hazel”:

“At 3:11 p.m., a section of approximately 25 feet collapsed into the street below, piling down on a lacework of electrical wiring which sent sparks shooting skyward. [Planks on the steeple] extending downward an approximately 20 more feet also fell before Hazel’s winds.” … City Building Commissioner William G. Wharton said he thought it “very improbable” now that repairs could or would be made, … he thought structural damage was such that demolition would be necessary” (Figure 7).[26]

The paper noted that the steeple had survived not only the “blizzard of 1896,” but also a 1951 tornado in which it had come through unscathed, but Hazel had proved to be too much. More of the steeple crumbled away two weeks after Hazel swept through, with timber falling from near the top and damaging three automobiles that happened to be parked beside the church.[27]

The razing of the old Trinity steeple began on May 23, 1955, despite bitter letters to the editor from people like Alice Smith, head of the Save the Steeple Committee, who said the group had raised $25,000 in cash and pledges to restore it. After it was gone, “to Richmonders long used to the familiar view on Broad Street east to Church Hill, the vista last week across Shockoe Valley had an essential part missing,” reported the Richmond Times-Dispatch.[28]

With the spire gone by June 1955, the beauty of West’s design of and Newell’s carpentry work on its base structure became more evident (Figure 8). By 1987, however, even more of it was gone than was taken down in 1955. The remaining tower support levels were described in the nomination form of the New Light Baptist / old Trinity Methodist Church for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places:

“The façade (of the church) is characterized by its three-stage central tower. The first stage of the tower features a wide arched doorway approached by a flight of splayed stairs. The original doors have been replaced, but the frame and the semicircular transom are intact. The second stage of the tower, which is separated from the first by a small cornice, features two arched reveals flanking a central arched window in its front. Similar arched reveals are on the lateral faces of this stage. A second small cornice crowns this stage. The third stage, which rises above the ridge of the gable roof, is octagonal in plan. Pilasters define each corner, and within the four main facets are Palladian-window motifs with their central. Arched elements fitted with louvers. A fourth stage and a spire, part of the original design, have been removed. The fourth stage was an open octagonal belfry, with arched sides and a small, bracketed cornice. … Photographs show the spire (also) of octagonal plan, rising to a point, without external elaboration” (Figure 9).[29]

EPILOGUE

Joseph Newell died on December 28, 1895, at age 73. [30] Of Joseph and his wife’s eight children, only Thomas and William appear to have carried on in the family business. When Joseph’s son, Thomas, died in 1934, his obituary noted he was the son of Joseph M. and Susan T. Newell, an “old and well-known family” in Richmond, and had worked for his father since a young man.[31] Joseph’s son, William, died in 1936. His obituary notes he was a partner in the building “and architectural” firm started by his father. William’s death certificate describes his occupation as “retired architect.” Like the architect West, who as an ardent Methodist may have been a family friend to the Newells, William would have followed the typical 19th century path from artisan to architect: the field did not begin to require licensing until 1897 when Illinois became the first state to require it.

The fictional account that opens this narrative speaking of the two sons who helped Newell build the steeple is a reference to Thomas and William.

[1] This account is an imagined scenario of the beginning of the factual work of completing the Trinity Church steeple. Newell’s tombstone in Hollywood Cemetery provides his birth date as December 31, 1822. The last name Liggon is spelled “Liggan” in some documentation.

[2] Edwin Slipek, “Up from the Asphalt,” Style Weekly (online: https://www.styleweekly.com/up-from-the-asphalt/), August 5, 2014. For more information about the architect West, see, for example, https://ncarchitects.lib.ncsu.edu/people/P000368.

[3] From a typed, informal biography of West located in the archives of the Virginia Museum of History and Culture (VMHC). The document is undated, but a contemporaneous mention of the date of 1968 puts the date at approximately that time. Pages 1-4 of the document provide specific details on West’s foray into military action, much of which appears to come from West’s diary which is currently in the uncatalogued collection of the VMHC.

[4] “Completion of Trinity Church – Interesting History of the Work,” Richmond Dispatch, October 4, 1873.

[5] “Local Matters,” Richmond Dispatch, July 11, 1855. The Richmond Times-Dispatch reported much later, in 1906, that the building had been “erected” by Pearson and Newell, but because it was brick, and masonry contracts were awarded separately, that would not seem to be the case (Pearson and Newell as builders: “Are Moving Out of Old Market,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, May 24, 1906; masonry contract: “To Builders,” Richmond Dispatch, July 1, 1854). It seems probable that Pearson and Newell were contracted to do just the carpentry work – whether in the entire building or just in this second story as described in the papers. In 1906, as reported in the Richmond Times-Dispatch, the First Market building was again judged to be in unsafe condition: a pillar had given way the previous year (it was replaced), the roof was in danger of tumbling in, and the building was “a little out of plumb, leaning slightly westward”). It is interesting that Pearson and Newell were still in 1906 associated with the building, but it isn’t known for certain how much of the original building had been their work or the work of others.

[6] “Necrology of the Year,” Richmond Dispatch, January 1, 1872.

[7] Joseph’s daughter, Susan, also known as Nannie or Annie, participated in a charity event at their church, Union Station Methodist, in 1866; and in 1886, the Newells hosted a delegate to a convention of Methodist men being held in Richmond. (“Children’s Fair on Union Hill,” Richmond Times, October 10, 1866, and “Methodist Men,” Richmond Times, April 25, 1886.)

[8] “Completion of Trinity Church – Interesting History of the Work,” Richmond Dispatch, October 4, 1873. The spire at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church at today’s 815 East Grace Street, said to have originally been at a height of about 225 feet, was significant in that it surpassed in height the state capitol building. It was removed in around 1905 out of stability fears and replaced by the much smaller, 135-foot, octagonal dome there today. (“St. Paul’s Episcopal Church,” Wikipedia, accessed May 23, 2025).

[9] Andrew Morrison, editor, Richmond, Virginia: The City on the James (Richmond, Virginia: George W. Engelhardt, 1893), p. 47.

[10] “Trinity United Methodist Church / New Light Baptist Church,” National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form (Washington, D.C., U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1987), Continuation Sheet 5.

[11] Madge Goodrich, Richmond, Virginia, “Trinity Church,” Virginia Historical Inventory, Works Progress Administration (WPA) 1936, p. 2. The “gem” description is a quote from Edward Leigh Pell, ed., A Hundred Years of Richmond Methodism (Richmond, Virginia: The Idea Publishing Company, 1899), p. 42.

[12] Mary Wingfield Scott, Old Richmond Neighborhoods (first published in 1950; republished Richmond, Virginia: William Byrd Press, 1984), pp. 169-170.

[13] “Hazel Writes Finis to Effort to Restore Trinity Steeple,” Richmond News Leader, October 16, 1954.

[14] “High Steeples of Richmond,” Richmond Times, February 11, 1900.

[15] “Great Storm,” Richmond Planet, October 3, 1896.

[16] “Church Steeples Must Come Down,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, October 27, 1911.

[17] “Says Unsafe Steeples Must All Come Down,” Richmond Evening Journal, October 26, 1911.

[18] “Church Steeples Must Come Down,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, October 27, 1911.

[19] Scott, Neighborhoods, p. 169.

[20] Scott, Neighborhoods, pp. 49-50

[21] Photo accompanying article, “Present Downtown Churches Determined to ‘Hold Line,’” Richmond Times-Dispatch, May 23, 1954.

[22] “Hopes Fade for Saving Old Steeple,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, August 3, 1954.

[23] Natalie Blanton, “Voice of the People: Pleads for Restoration of Old Trinity Church,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, August 7, 1954.

[24] “Landmark,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, August 29, 1954.

[25] “Hopes Fade for Saving Old Steeple,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, August 3, 1954.

[26] “Hazel Writes Finis to Effort to Restore Trinity Steeple,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, October 16, 1954.

[27] Photograph, “A Witch’s Curse,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, October 31, 1954.

[28] “Old Trinity Steeple is Demolished,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, May 29, 1955.The tearing down of the steeple was accompanied by much controversy reported in the Richmond press from this time forward for several months. The steeple wasn’t the only part of the church in bad need of repair: the roof had also been deemed unstable because of serious rainwater leaks causing the building itself to be considered unusable until the roof was repaired. In the end, the building was saved but even today remains without a steeple. Some of the reporting of the time unfortunately diminishes or ignores the fact that the church was by then the New Light Baptist Church.

[29] “Trinity United Methodist Church / New Light Baptist Church,” National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form (Washington, D.C., U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1987), Continuation Sheets 1 and 2.

[30] E.g., “News from City Hall, “Richmond Dispatch, January 21, 1896; “Commissioners Notice,” Richmond Daily Times, April 1, 1896; “Property Transfers,” Richmond Dispatch, April 3, 1901.

[31] “Thos. D. Newell, contractor, dies,” Richmond News Leader, July 26, 1934.