May 31, 2007

We lived in a green aluminum house on West Holland Street. It was a pretty big deal to have aluminum siding when all the neighbors still had brittle asphalt shingles on theirs. My dad and brother dug big holes on both sides of the gravel driveway and stuck tree trunks in them, then ran a board across the top and hung another short cedar board from it with Lazy C (the C was cock-eyed so you could tell how lazy it was) burned into the wood by the same artistic-leaning brother with his new wood-burning set he got for Christmas from Woolworth’s. The roof of our house was shiny silver corrugated tin, and there was no better place to be when it stormed than in the attic where you could listen to the rain falling, magnified to Wagnerian proportions.

When we moved there in 1958, Daddy bought the 38 acres of land, three “houses” and a red Ford tractor, taking out a mortgage for the $5,000 purchase price. The house we lived in had four rooms, all the same size, 13×13 feet, set like a four-patch quilt block save for the steep stairway in the center of the arrangement going up to the attic. Each room had two doors, each door in the very middle of two adjacent walls, and each door led to a different room, so one could wander endlessly in a squared-off circle around and around the house. The exception to this efficient design was the room we used as a kitchen which had another door toward the center of the house that led to the attic. The house did not have the green aluminum siding or the tin roof in 1958, of course. These were later upgrades.

Sometime before we bought the place, the house had been picked up by a tornado, turned around exactly 180 degrees and set back down more or less in the same spot as it started, except the front was the back and the back was the front. Due to the inspired design of the house, this didn’t create any significant architectural incongruencies. There were no plumbing difficulties either, because there wasn’t any plumbing.

Daddy was handy, and he and his Dad, who I remember resembled Abe Lincoln, being tall, thin, and somewhat homely, began work right away to upgrade the purchase. They added a long, rectangular room to the west side and then carved about a third of this space into an indoor bathroom. This was done relatively quickly. My mother was, after all, Californian, and then, as now, Californians had the reputation for being a little different from the rest of us. It was quickly apparent to my father that her sensibilities were not the sort for making do with an outdoor privy for long, even if it was a luxury, two-holer model. My main problem with the outdoor arrangement, being barely three years old, was having to chase the chickens out of the privy in order to go inside. It is unnerving to go the bathroom with chickens watching your every move, and the chickens had a vicious nature, or at least, so I thought. Dealing with those chickens was a terrifying prospect; it remains as the earliest memory I have of my life.

Sometime shortly after this, Daddy and Grandpa also dug the lake out back. There was a convenient creek that lay through the property, and Daddy rented the mid-1950s version of a backhoe and dug a big hole, a really big hole, and scooped out an earthy umbilical cord to tie it into the creek. He pushed the leftover dirt from the depression he had created and built a berm around it so he could drive his pickup around the rim. He knew enough about engineering to build a concrete spillway to let water in and out of the lake when too much rain fell during those storms which I loved to listen to up in the attic. This hole was then a lake. My family never called it a “pond,” and it was offensive when someone did. The berm, likewise, was a “levee.”

The spillway had a heavy guillotine-like iron plate that was lifted by a built-in lever in order to release water when Mother Nature got overly exuberant with rainfall. I’m certain Daddy designed this apparatus and had it custom-made; I can still remember the bubbly welding marks which held the rusty pieces together. Barrels laid end to end with their tops and bottoms removed formed a channel in the cement through which the water could escape. A few years later, Daddy had the presence of mind to design a fish trap on the far side of the spillway from the guillotine. When the lake was high and the skies were still angry from a recent storm, he and I would walk back to the spillway. I’d watch him push open the guillotine with the lever, and then we’d both run over to the other side and watch the water gush through. Daddy had built a cement ledge there and encircled it with chicken wire, and he would delight in the size and number of fish caught, all having grown from the little minnows (practically) with which he had stocked the lake with his own hands. Bream, crappie, sunfish, and bass. His mom, my daughter’s eventual namesake, loved to fish, and Grandma and Grandpa had moved next door by this time into one of the little shacks we, who loved euphemisms when we talked about our place, called the renters’ house. Daddy would gather up the fish from the trap and throw them back in the lake because it wasn’t a sportsmanlike way to fish.

It was a stretch of the truth to call the dirt road in front of our house a “street.” And the name “Holland” implies a certain international cachet that was non-existent in this corner of Jefferson County. Our mailing address was Route 4, Box 783, and it was a great embarrassment to me to live on a “route.” We didn’t even pronounce it the cool way like they did on tv: it wasn’t “Root” as in “Route 66.” We lived on plain old “Rout.” I didn’t understand why we couldn’t just live on 783 West Holland Street and still to this day hold this against the postman.

Unlike my mom the Californian, Grandma was satisfied with the outdoor toilet facilities at the renters’ house, leaving Grandpa and Daddy time to begin their next project: the barn. We had moved to this corner of nowhere on West Holland Street because a year earlier he had bought a print shop on Barraque Street in town. There was more opportunity in Pine Bluff than in Camden, he thought. We had lived in the back of the shop for a while, and then Daddy found this little spot of paradise which now included an indoor bathroom and a lake.

I believe I have some memories of the barn being built, but they are vague. I know that Mom marveled at my Dad’s architectural capabilities to design the barn, and as I grew up and became familiar with every inch and every cobweb, I too was impressed at how this man with only an eighth-grade education could put together such a marvelous thing. I loved that barn. It was sited behind the lake in a little stand of pine trees. One of these trees had grown in a peculiar way: the trunk had doubled down and then back up like a sideways S, leaving a spot about five feet up big enough for Momma to sit in. Once, Daddy lifted her up there and took her picture.

Daddy and Grandpa built the barn out of rough-cut gum. It was two stories with a large center passageway running the length of it on both the bottom floor and the loft. The loft was accessed by climbing through a hole in the floor via a ladder built of boards nailed without the troublesome use of a level to two vertical 2x4s about 18 inches apart attached to a support beam at the floor of the loft. Only relatively slender people had access to the upper level of our barn on that ladder. The bottom floor of the barn was dirt originally, but over the years it became covered with a sweetly-fragrant carpet of manure from the cows and occasional horse we kept. (Mama confided to me one time that she always liked the smell of cow and horse manure, and though I never would have admitted to it at the time, so did I.)

Hay and junk were stored in loft. At both ends of this upper part, Daddy built big, heavy double doors that could be swung open with a grand gesture. Daddy designed a precipice on one side of the floor upstairs. He ran 2x4s, spaced about 14 inches apart, from the back of a counter-height, three-board-wide shelf that was accessed from the bottom story of the barn, up at an angle to the far side of the precipice in the loft. This was the manger. The design allowed us to throw hay through the opening at the top where it would fall into the bottom of the V. The boards were spaced just far enough apart that the cows and sometime-horse could reach their heads between the boards and yank the hay out. It was an ingenious design. I’m sure Daddy didn’t invent it, but it was impressive that he was able to replicate it. Daddy would tuck a green-colored salt lick under the shelf, more for the deer which would come by to check things out than for the livestock we had. On one side of the ground-floor hall was an open stall area, and on the other side was an area for feeding those cows and occasional horse. A nice-sized feed room — Daddy was not known to be chintzy with this sort of thing — took up some of the space on this side of the barn. Daddy stored feed bags of corn and oats there, the kind where the bags were made of fabric that Grandma would save to use for making my play clothes.

When I was older, my friends and I used to crawl all over that barn. At one point, Momma stored a rusty old iron bedstead in the loft. It was the old-fashioned kind that had the springs built in. Lordy, we spent hours and hours jumping on that thing with the upstairs doors of the barn splayed wide open to let in a little breeze. I didn’t think there could be anything funner to do in the whole world. If my friends weren’t around to play, I’d go back there and bounce and bounce and bounce all by myself.

One particular year, Daddy stored so many bales of fresh hay in the loft, that it was hard to squeeze by them to get to the bouncy-bed. It all smelled heavenly, even better than the manure down below. It seemed the right thing to do to pull some slices of the hay out of the bales (wonder of wonders — only people who grow up on a farm know that hay comes apart in slices) and throw it into the V-shaped hay holder (I’m sure there is a technical name for this) for the enjoyment of some passing cow. The hay must have been intoxicating, I kept pulling it and tossing it, pulling it and tossing it. Now here was a new athletic attraction: I could jump down on it in that V like a stuntman in a John Wayne movie. The hay broke my fall. After the first time, when I crawled between the supports onto the shelf and realized all my limbs were intact, I realized this was just as much fun as jumping on that bed. The whole process was addictive, and so it clearly was not my fault as I kept it up until I had those hay holders stuffed and packed with so much hay that not even the hungriest cow would be able to manage to jerk a mouthful of it from between the boards. About halfway through, I knew I was going to be in trouble, but I also knew I would be in the same amount of trouble for filling those hay holders up halfway as I would be for filling them up entirely, so I figured I might as well have the fun. That evening, I climbed a sycamore tree in the backyard and waited for Daddy to come home. I watched him park at the side of the house, go in to check in with Momma, then drive his truck across the levee back to the barn to feed the cows. When he came back, he parked the truck at the side of the house, and I watched him walk into the house. I stayed in the tree until dark, but knew it was no good. I was going to have to face him. He never said a word, even though I was the only possible culprit. And I never did it again.

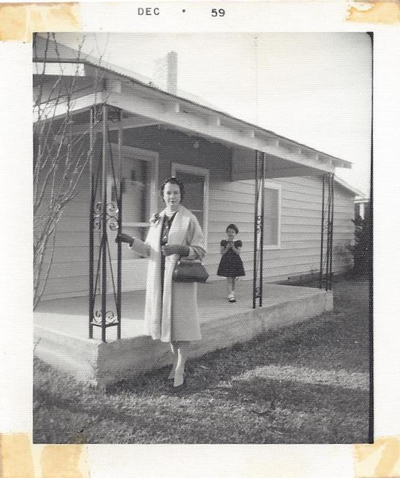

Looking back at old pictures and studying the dates that were printed on them when they were printed, it can be seen that Daddy accomplished all this at a record rate. Pictures dated 1959 show the house with the side addition, and the green aluminum, and the corrugated tin roof. It also shows that Daddy had already built the front porch. (Daddy seemed to have had a list of things, probably influenced by Momma, he needed to have in order to have the perfect house.)