The story of a Richmond physician who practiced medicine in Richmond, Virginia, from the age of 17. He died in 1950.

(This is a slightly edited version of information excerpted from the PDF about the social history of the house at 2720 East Broad, Richmond, Virginia. More details appear in the PDF.)

February 23, 2025

It always starts with a knock on the door. It’s not the three taps of a neighbor asking to borrow a cup of sugar: it’s at least five quick raps, an intense thumping of knuckles on wood. Even a few seconds must seem interminable to the visitor, and so they knock again too soon. This time the soft side of their fist strikes the door – not like a blow in a physical quarrel, exactly, but going in that direction. Inside the house, the inhabitants know those knocks. They put down their newspaper, or their fork, or their pipe. Before opening the door, they put a mask of professional concern on their face in case what they see might provoke instead a spontaneous expression of increased emotion. On the porch is a man, holding one arm with the other, ripped strips of dirty linen wrapped around wounds, blood spots present but not spreading. It was the older woman next to him who had panicked in announcing their presence. A younger one – their daughter? – stands back, looking more afraid than worried.

Come in! Come in! (It was the good doctor who had answered the door this time.) Through here, he says, gesturing past the pocket door and then reaching out to help support the injured man under his good arm. The wounded man barely steps into the next room before sinking into the chair kept there just for this purpose.[1]

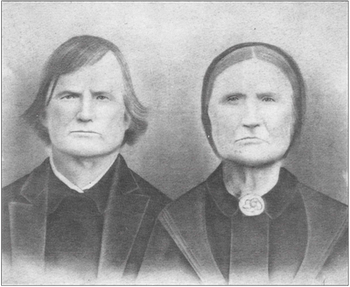

Dr. George W. (for Washington) Gay had been living in Richmond since 1895, but his childhood had been spent in the village of Scotland Neck in Halifax County, North Carolina. Born there in 1881, he lived in an area where his ancestry ran deep, at least back to the time of the American Revolutionary War, and where he was surrounded by an extended family of many cousins, aunts and uncles, and other relatives that today would be identified as once- or twice-removed in a family tree. His grandfather, Dempsey Gay, born in 1815 and at least the second in the line of the family’s Dempsey Gays, had had eleven children. Family lore has it that Dempsey and his wife Mary were part Native American, that they were wealthy, and that were hard workers. The presence of native blood in their veins was likely untrue as it is for many American families who have the same mythology in their origin stories.[2] The report about their wealth is probably also exaggerated; the census of 1850 shows Dempsey Gay having real estate valued at only $300 (this was about middling compared to other farmers listed close to him in the census; there were others with land valued in the several thousands), and his tight-fisted father had left him and all but one of his siblings only one dollar (about $36 today) when he died. (A brother received the deceased Dempsey’s land). The story about being hard-working, however, seems likely to be true given their financials and the fact that they had only one enslaved person, a 17-year-old boy, working their farm (some neighbors had enslaved persons numbering in the twenties). A remarkable photo of Dempsey and Mary, likely taken in their 50s, show them as a somber couple, his eyebrows furrowed, and her lips turned down (Figure 1).[3] They likely were descendants of the groups of colonists of English or Scots Highlander lineage who had settled in North Carolina at the “neck” of the Roanoke River as early as the first quarter of the eighteenth century.[4]

George Gay was born in Scotland Neck on August 7, 1881, during a time of prosperous growth for the village which had been spurred on by the arrival of a branch line for the Wilmington and Weldon Railroad. With a population of about 2,500 people, there were 34 mercantile establishments, including two drug stores and two dry goods stores as well as a post office and five saloons. By 1884, there were several small manufacturing enterprises making agricultural implements and coaches and carriages, and six mills processing corn. Churches were built, banks were founded, and physicians and attorneys established practices. A private academy for the education of boys was opened.[5]

Even so, the Gay family moved to Richmond in 1894, a move likely precipitated to exploit educational opportunities for their two precocious sons: George was a boy of 13 and his only sibling, William Dempsey Gay – known as Dempsey – was 15. It was a straight shot from the new railroad station in Scotland Neck to Richmond and would have been less than a day’s journey. In Richmond, George’s father, 34, also known as George W. Gay but with the middle initial substituting for Wesley, was self-employed as a carpenter, specializing as a “bracket maker,” perhaps a reference to the gingerbread often present on Victorian homes of the era. George’s mother, Laura Elizabeth, 40, was a dressmaker and, like her husband, was listed in the 1895 Richmond City Directory. Since it was rare for women at the time to be mentioned in the directory, it likely means she was highly skilled and sought-after. The family was living at 807 North 24th Street in Richmond, in the Union Hill neighborhood (Figure 2).[6]

Both Dempsey and George were exceptionally bright young men. Dempsey, the older by two years, received his diploma from the highly-regarded Scotland Neck Military Academy at the age of 13. While the family was still in North Carolina, he entered Wake Forest College (now University) law school as one of its earliest students, attending four sessions (apparently four years), moving on to Richmond College (then on Broad Street but now the University of Richmond in Richmond’s Near West End) once his family moved here. He graduated with distinction in 1898, but since he was only 19, he had to wait two years before taking his legal examination before the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals; he passed it in Wytheville in 1900.[7]

As a young boy, George attended private school in Scotland Neck (likely Vine Hill Academy) and then, like his brother, also attended the military school there. After the move to Richmond, in 1894 at the age of 13, he studied at Richmond College where he studied Latin, English, and Mathematics, leaving without a formal degree.[8] He entered the University College of Medicine (UCM) in 1895, one of two medical training institutions in Richmond at the time – the other being the Medical College of Virginia (MCV). UCM, founded in 1893, was considered to offer a more practical medical experience and more clinical practice than did MCV; and at the time, it was a three-year program that only required a high school education or a teacher certificate for admission. The two merged in 1913 and in 1968 became the VCU School of Medicine, as it is still known today.[9] George passed the Virginia State Board of Medical Examiners in July 1897, receiving his license at the age of 15. He graduated from UCM in 1899 and began practicing medicine in Richmond as a resident physician at the Richmond Home of the Incurables.[10]

Dozens of newspaper articles reported on Dr. Gay over the years of his practice, particularly the first couple of decades. He was first mentioned in the press in January 1900 when he was elected a fellow of the Richmond Academy of Medicine and Surgery, an organization founded in 1820 to allow doctors to engage in continuing education endeavors and discuss other kinds of professional concerns. [11] It is still active today. In February, the first article to address Dr. Gay’s professional skills suggested that he had likely saved the life of Richmonder John Wilson who had taken an accidental overdose of Epsom salts. The paper reported that the overdose had caused Wilson to suffer “anemia of the brain.” Dr Gay was “hastily summoned, and by prompt work revived the sufferer, though Wilson had been unconscious for at least ten minutes.”[12] The following June, the press noted that Dr. Gay performed surgery, probably his first, operating on a Richmond man to remove a tumor. Four days later, the local paper reported the operation had been a success, that the man was “getting along very nicely” and his speedy recovery was “anticipated.” The 19-year-old Dr. Gay had been assisted by Dr. R. L. Kern, at 29 older than Gay, but like Gay, had graduated from UCM only the year before.[13] Dr. Gay did not always achieve success. In July, he had been unable to save a woman who received serious injuries after being run over by a streetcar. [14]

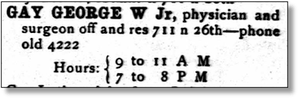

Gay was associated with the Home of the Incurables for only one year. By 1901, he was receiving patients in the family home at 711 North 26th. He had established office hours – from 9 to 11 a.m. and from 7 to 8 pm – at his home, advertising himself as a physician and surgeon (Figure 3). He had an early telephone in Richmond, and could be called at 4222 in 1901, a number which changed to MOnroe 3134 by 1902. The entire Gay family (his father, his mother, and his brother) lived at North 26th at the time (the house still stands at the address today, Figure 4). [15]

Dozens of articles reported Gay treating very serious, even horrific, cases: patients presenting accidental poisonings or burns as well as those who had been involved in industrial or construction accidents, transportation accidents (involving cars, trains, and streetcars), or gun violence. The majority of his practice seems not to have been made in his home, but rather through house calls.[16]

It was not all work and no play for Dr. Gay. His name often appeared in society columns as attending parties and other social events. In March 1905, George was in the wedding party when his brother married the former Julia Clare Bickers.[17] In March 1907, on the second anniversary of Dempsey’s wedding, the family – Julia had moved in with them – threw a bash at their home at 711 N. 26th: “From half-past 8 until a quarter of 12, the parlors of the hospitable Gay home were filled with a congenial company of guests who entered into the spirit of the occasion with zest and highly enjoyed themselves.” Professor Ernest L. Bolling and Beulah Burch played the piano, the Church Hill Mandolin Club performed, and Aida Lee Allen gave “several fine” recitations. Some 60 people were listed as having attended.[18]

In 1908, Dempsey, 29, George’s brother, died. A cause of death was not provided, but the paper reported he had been ill for several months. The press provided details about Dempsey’s remarkable education at an early age, noting that “being thoroughly in love with the law, and possessed of a remarkably keen analytical mind, his success was assured from the first.” The article added, “Up to the time of failing health, he was enjoying a growing practice and had before him brilliant prospects. His remarkable adaptedness to his profession, coupled with his studiousness and affability and his unswerving loyalty to high ideals, won him many friends.” In addition to his widow, Dempsey was survived by a “bright little two-year-old boy” named after his uncle.[19]

It must have been a hard blow to this small family, and especially hard for Dr. Gay who, despite being a physician, was unable to help his brother with his medical crisis. But they moved on. Julia, George, George’s father and mother, and little George would continue to live together for the rest of their lives.

The Purchase of 2720 East Broad and the Life of the Doctor

Dr. Gay, as well as his father and Dempsey, had begun buying and selling real estate in Richmond as early as 1903, especially in the Union Hill and Church Hill neighborhoods.[20] On September 14, 1911, George Gay bought the property at 2720 East Broad. It would house not only his family but also his medical practice, advertising in the city directory once again his hours there as 8-10 a.m. and 7-8 p.m. His telephone number was MAdison-3134.[21]

In 1910, Dr. Gay bought a car, a Maxwell 30 (Figure 5). His was a white, seven-passenger, steamer touring car with 40 horsepower – steam-powered cars outnumbering other forms of propulsion among automobiles in the early 1900s. But early steam cars required constant care and attention and an exasperatingly up to thirty minutes to start. Possibly even more inconvenient was the fact that they needed to be refilled with water every twenty to thirty miles. In 1911, Gay loaned it to delegates attending a spring Methodist Women’s Mission Conference meeting in Richmond who used it and other automobiles loaned to the group to give a “much-enjoyed” ride to the Methodist orphanage. The next week, his name appeared in a list of 375 automobile owners in violation of a Richmond City ordinance requiring registration of motor vehicles. He put it up for sale a month later.[22]

Over time, Gay seemed to have developed a reputation such that people would bypass other, more convenient, expressly to seek his attention. That was the not-isolated case in July 1916 when M. L. Compton, “a widely-known citizen of Louisa County,” showed up at Dr. Gay’s door at 2720 East Broad. Compton, accompanied by his wife and daughter, arrived there early one Monday morning, having first been driven to Ashland in an automobile from Yancyville, and then traveling from Ashland to Richmond on the electric cars. Compton and his neighbor, Frank Jones, had had a falling out the day before, and it had ended with Jones shooting Compton. As it turned out, Compton suffered only flesh wounds in his left arm, right leg, and abdomen, and he returned to his home after receiving treatment with Dr. Gay. The neighbor had been less lucky: he was shot and killed by Compton’s 15-year-old son. (The boy was exonerated at a coroner’s inquest.) [23]

Over the years, Gay continued to be an active participant in medical societies on a city, state, regional, and even nation-wide basis, showing a wide-ranging curiosity in his chosen profession. Among many other examples in the press, he discussed “diagnosis” at a degree conference at UCM and participated in a study of a new treatment for tuberculosis (then called “consumption”) at the Methodist Institute.[24] He presented a paper on the effects of alcohol on the human system at the meeting of a state organization and discussed a paper on typhoid fever at the Church Hill Medical Society on June 28, 1907.[25] In perhaps the most remarkable example of Gay’s variety of interests and his wide-ranging contacts was the publication in 1920 of his observations in a study of uterus displacements in Surgery, Gynecology and Obstetrics. Gay reported two case studies to the author of an article in the publication – the first involved a 30-year-old woman whose uterus had to be manually re-placed (and who recovered from the ordeal), and the other a French poodle which had suffered a complete inversion of the uterus with placenta attached. In the case of the dog, the placenta was removed, the uterus reinverted, and the dog also recovered. [26]

His work may have put him at bigger risk of becoming sick than that of others might: In 1903, Gay was reported ill “all the week,” and was reported again in 1925 as having improved “slightly” and “will recover” after “another” serious illness.[27] The biggest crack in a seemingly robust life, however, was in October 1932, when he was 52 and he underwent two surgeries described as “major operations.” He spent two months convalescing. Even so, he made sure the papers announced in November he had resumed his medical practice “at his office at 2720 East Broad.” [28]

The extensive reporting in the local press over the years reflects the story of a man not only interested in his profession but also in service to his community. In 1903, Gay, 22 at the time, along with Dr. Kern, volunteered to work pro bono at the Methodist Institute located at 19th and Main for an hour three days a week in service to the poor.[29] In 1904, Gay and Dr. Kern established the Sarah Wiley Memorial Hospital at the Methodist Institute also for poor patients. Gay and Kern both donated their services at the hospital but additionally set it up to allow UCM interns to gain professional practice.[30] Dr. Gay donated to charities: in 1918, he bought at least $1,000 in War Bonds.[31] He contributed to the Christmas-season “Neediest Family Funds” and later the “Christmas Mother” charity at least four times.[32]

Dr. Gay seems to have been an avid newspaper reader and enjoyed engaging with the local press by entering contests or in other ways, at times showing a bit of an eccentric side. He won a ticket to a show at the Academy playhouse as one of 300 entries in a June 1913 contest for sketching the character of a devil that had appeared in a previous show, and he won $5 twice as the top prize and $1 once as a runner up prize for entering anecdotal stories about Richmond trivia in local newspaper contests in 1929. [33] In 1935, he collected $1 for a bit of trivia he submitted to the Richmond Times-Dispatch about Napoleon and Willington avenues in Richmond. In 1936, he wrote a letter to a fishery columnist telling of the catching of a 45-pound stingray in the Rappahannock that “gave birth to a baby ray” shortly after being thrown on the deck. It wasn’t clear whether Gay had caught the ray or even been present when it was caught, but somehow, he had come in possession of the dead animal which he kept in a jar of alcohol. [34] In 1938 Gay sent an object to the Richmond News Leader “looking something like a chipped off marble, but more like a hazel nut” and invited the reporters to guess what it was. They couldn’t, and so he let them in on his secret. It was the petrified white and yolk inside part of a pullet’s egg (one laid by a less-than one-year-old chicken). He said that five years before, he had been given two such eggs, which he had put in one of the drawers of the desk in his office. They had remained there, forgotten, until recently when the shell of one of them broke off and reveled the petrified inside, “hard as stone and with very rich colors.”[35]

In 1929, in a letter to the editor of the Richmond News Leader, he anonymously wrote about himself as being a bit of an oddity:

“Sir. – In your paper this afternoon there is a news item which says Harold M. Finley, McConnelsville, Ohio, registered as a freshman this week at Northwestern University at the age of 13. In our dear old Richmond, there is a physician (whose name modesty forbids my mentioning), who entered Richmond College at the age of 13, began the study of medicine at the University College of Medicine at the age of 14, passed the full medical state board at the age of 15 and graduated in medicine with the degree of M.D. at the age of 17. [Signed,] George Gay.”[36]

It is, of course, obvious to those who know Gay’s story that the reason for “modesty” was because he was describing himself, but in any case, a few days later, Henry G. Blanche, a watch man at Planters Bank and Trust Company revealed Gay’s identity in a follow-up letter to the editor. Calling Gay his “beloved friend and family physician,” he said in his letter that Richmonders should know who this physician was “who [had] made such a remarkable record.” He added, “And everyone who knows Dr. Gay knows he has made a wonderful success in his profession and nothing too good can be said about him.”[37]

Later, in 1932, Gay expressed in a letter to the editor of the Times-Dispatch a great fondness for his adopted hometown of Richmond and imparted a bit of his philosophy for life:

“Sir. – (Regarding) the discussion in the Voice of the People [letters to the editor column] concerning the hospitality of the South, I cannot imagine how anyone can fail to appreciate the friendly feeling which exists in Virginia. I arrived in Richmond in the nineties at a period when times were so hard that the present condition of affairs looks like a gold strike, and I have never found anything but friends and the kindest treatment, and it is my opinion if you cannot find real honest to goodness friends here it would be a hard job to find them anywhere on earth. As a physician, it has been my experience that in case of sickness there has never been any lack of aid, when needed, among those people whom I am fortunate enough to number as my friends and patients. If you want friends, be friendly. [Signed,] George Gay.”[38]

Over the years, Dr. Gay continued to buy and sell numerous properties, many, but not all of them, in the Union Hill and Church Hill neighborhoods. Many of them were homes or lots, but he also would occasionally be involved in larger transactions. In 1910, he bought the “old” Seventh Day Adventist Church on 33rd Street.[39] In two transfers in May 1912, described as some of the biggest by Richmond brokers that month, he bought a 381-acre farm in Louisa County and sold a building at 2420 East Broad for $21,000 (the latter torn down in the early 1960s with the property becoming part of Patrick Henry Park). [40] He owned an unknown number of apartment buildings.[41]

Life in Later Years

Though Dr. Gay may have owned other cars after the Maxwell 30, in 1935 he bought another car, this time an Auburn coupe.[42] Though the make and the model are unknown, the Auburn vehicle of the day was considered to be fast, good-looking, and expensive (Figure 7). [43]

There is no known existing photograph of Dr. Gay, although the required registration form he filled out for the military draft in 1918 offers a hint of a dashing figure: he was tall and of medium build with blue eyes and brown hair (there is no evidence that he was ever called to serve). He no doubt would have been a striking presence parking his Maxwell 30 in front of his home at 2720 East Broad.

As Richmond’s population increased and what constituted “newsworthy” reporting changed, fewer articles appeared after about the 1930s of Dr. Gay’s work. The last known article appeared in the Richmond Times-Dispatch, when Dr. Gay attended to Jefferson Curry Powers, 72, after he had collapsed while presiding over a meeting of the board of stewards of St. James Methodist Church at North 29th and Marshall streets. Powers died before Gay could reach him.[44]

The Death of Dr. Gay

Gay’s mother, Laura Elizabeth Carlisle Gay, 75, died in 1928. His father, George Wesley Gay, 80, died in 1930. Dr. Gay, his sister-in-law Julia, and his nephew continued to live in the house at 2720 East Broad through Dr. Gay’s death at 69 on August 27, 1950, of what was labeled on his death certificate a likely ruptured aneurysm of the brain. Despite Gay’s remarkable life and career, the obituary was surprisingly modest. It made a short reference to his medical training (that he had received his medical degree at the age of 17 from the old University College of Medicine and that he had interned at the Home for Incurables), and added that he had practiced medicine for more than 50 years and was a member of the Richmond Academy of Medicine, the Henrico Union Lodge 130, A.F. & A.M. (Freemasonry), and Woodmen of the World.

From all indications, Dr. Gay had continued practicing medicine out of his home 2720 East Broad through the entirety of his life. He reported to the census taker on April 6, 1950, only four months before his death, that the majority of his time the past month had been spent working.[45] To the 1940 census taker, he had reported working 84 hours the week prior as a medical doctor.[46]

The probate of Dr. Gay’s was published in the press, a not-terribly uncommon occurrence of the time. The life-long bachelor left the bulk of his $330,480 estate, which consisted of $180,480 in personal property and $150,000 in real estate, as a lifetime trust for the benefit of his nephew, George Gay, III. The will also bequeathed to Genevieve Nance Bootright “any one of my apartment houses in the city of Richmond” to be selected by her within a period of six months after his death, along with a 196-point diamond ring. To Violet Parker Cousins, he bequeathed another $10,000 in securities “of her own selection” as well as a 65-point diamond stickpin.

Bootright and Cousins appear to have been trusted colleagues and friends who may have helped him with the non-medical side of running his business. The unmarried Bootwright, 57 at the time of Dr. Gay’s death, apparently was an independent bookkeeper. Though she had lived in Richmond most of her life, she was apparently living with her brother in Fredericksburg when Dr. Gay died. In 1955, five years after Dr. Gay’s death, she was living at 2800 Park Avenue, Apt. 5, presumably in the apartment building she had picked.[47] The unmarried Cousins was 45 at the time of Dr. Gay’s death and a clerk at an insurance company.[48]

Gay made six smaller, but not insignificant, bequests of $500 to $2,000 to other relatives and friends, all of them women. He further instructed in his will that his body be cremated, and that his ashes be buried “at the feet of my dear mother” in Oakwood Cemetery.[49]

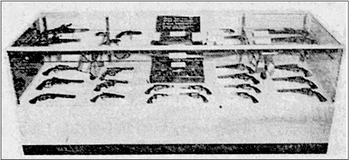

Shortly after inheriting his uncle’s estate, the younger George Gay revealed yet another unconventionality about his uncle: Dr. Gay had collected guns over the years (Figure 8). Lent for display to the First and Merchants National Bank of Richmond in January 1951, the local newspaper called it “a rare Richmond collection of weapons, curious and historic, which have been used in all the wars in which the United States was involved before 1900.” According to the paper, although Colts predominated, one of the oldest in the elder Gay’s collection of 74 guns was a 1700 pair of flints marked “Wogdon, London.” There was also a “saloon pistol,” which the paper said was used around 1890 to “shoot for drinks”; the percussion, .46, center-hammer gun was built to fit into the leg of a boot without slipping down. Another gun on display was a flintlock pistol with a brass barrel and attached bayonet which was described as used for close-up fighting at sea. A derringer which could fit into a vest pocket and was popular with steamboat captains and for “over the table” shooting was included. In addition, there was a “pepper box” revolver, popular in the West and the North; a Wells Fargo colt made “as light as possible” for use by the Pony Express, and a “very Pistol” used for signal purposes and was described as comparatively modern. One of the Colts had a stagecoach scene engraved on the cylinder.[50]

The estate put the collection up at auction the following March, but no word of its dispensation could be located.[51]

[1] This account is an imagined scenario of the 1916 arrival to Dr. George W. Gay’s home by M. L. Compton and Compton’s wife and daughter from Louisa County.

[2] Online family trees reveal no relationship of this family to Native Americans.

[3] Information in this paragraph is based on original documentation (such as the 1850 census) available on www.ancestry.com as well as on family trees posted on the genealogical site by those who are Dr. Gay’s extended relatives.

[4] National Register of Historic Places, Nomination Form, “Scotland Neck Historic District,” Halifax County, North Carolina. United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, October 31, 2002.

[5] National Register of Historic Places, Nomination Form, “Scotland Neck Historic District,” Halifax County, North Carolina. United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, October 31, 2002.

[6] Move to Richmond in 1894: Mrs. Madge Goodrich, “Gay Home,” Works Progress Administration of Virginia Historical Inventory, October 22, 1937. Goodrich appears to have spoken to Dr. Gay personally. Employment and residence: Richmond City Directory, 1895, p. 336.

[7] “W. D. Gay Answers Call,” Richmond Dispatch, December 28, 1908. Both this obituary and another appearing in another newspaper have Dempsey’s birth year incorrect as 1887, perhaps the mistake of a distraught relative. The detail in the obituary is unusual for the time, indicative of the high regard Dempsey was held in the community. The 1898 Spider, yearbook of then Richmond College, confirms W. D. Gay received a “Bachelor of Law” (p. 124).

[8] Personal correspondence with Darlene Slater Herod, Virginia Baptist Historical Society (Boatright Library, University of Richmond), September 9, 2024; “George Washington Gay, Jr.,” Richmond Academy of Medicine questionnaire, July 6, 1934, available at Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) Special Collections and Archives.

[9] Personal correspondence with Margaret Kidd, senior curator for Health Sciences, Special Collections and Archives, Cabell Library, VCU, September 13, 2024.

[10] “Dr. G. W. Gay, Aged 69, Dies in Hospital,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, August 28, 1950; Madge Goodrich, “Gay Home,” Works Progress Administration of Virginia Historical Inventory, October 22, 1937; University Medical College; Richmond City Directory, 1899, p. 334 (lists Gay as a resident physician at the Home for the Incurables). George, though younger than Dempsey, attended Richmond College before his brother and, unfortunately, before yearbooks were published. The former Virginia Home for the Incurables is known today as The Virginia Home and is located in the Byrd Park neighborhood. It is the only facility of its kind in Virginia to provide residential, therapeutic, and long-term nursing care of adults. It is home to 130 men and women from across Virginia. The facility where George Gay worked in 1899 was the second of three and was located at West Broad and Robinson. (Source for background on the Virginia Home of the Incurables: “The Virginia Home: then, now, and tomorrow,” thevirginiahome.org, accessed August 30, 2024.

[11] “Academy of Medicine Meeting,” Richmond Dispatch, January 24, 1900.

[12] “Overdose of Salts,” Richmond Dispatch, February 8, 1900.

[13] “Successful Operation, Richmond Dispatch, June 17, 1900, and “Local Matters,” Richmond Dispatch, June 21, 1900.

[14] “Mrs. Evans Dies from Injuries,” Richmond Dispatch, July 26, 1900.

[15] Richmond City Directory, 1901, p. 369, and Richmond City Directory, 1902, p. 374.

[16] E.g., “Mr. Burnett Improving,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, July 31, 1910.

[17] “Gay-Bickers,” Richmond Ties-Dispatch, March 1, 1905.

[18] Wedding Anniversary,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, March 3, 1907.

[19] “W. Dempsey Gay,” Richmond News Leader, December 28, 1908, “W. D. Gay Answers Call,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, December 28, 1908.

[20] E.g., “Property Transfers,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, April 17, 1903.

[21] Richmond City Directory, 1912, p. 489.

[22] “New Automobile Registration,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, August 4, 1910; “Unification of Both Missions,” The Virginian, May 18, 1911; “Many Licenses to be Secured,” The Virginian, May 24, 1911; classified advertisement, Richmond Times-Dispatch, June 21, 1911. Gay had registered the car with the state, but not with the city, apparently.

[23] “M. L. Compton Wounds Not Serious,” Richmond Virginian, July 18, 1916; Wounded Man Saved by Son Returns to Louisa,” Richmond News Leader; “Compton Returns Home,” Richmond Virginian, July 20, 1916.

[24] “Confer Degrees on Medical Men,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, May 18, 1905; “Consumption Can be Cured,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, October 24, 1905.

[25] “White Ribboners Hold Convention,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, March 7, 1903, and “Discuss Typhoid Fever,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, June 28, 1907.

[26] Franklin Henry Martin, “Acute (Puerperal) Inversion of the Uterus,” Surgery, Gynecology & Obstetrics, June 1920, page 46. Franklin Henry Martin, of Wisconsin, was the founder of the Journal of the American College of Surgeons and established the journal Surgery, Gynecology & Obstetrics in 1905.

[27] “Dr. Gay Better,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, February 8, 1903; “Dr. Gay Improving,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, September 20, 1925.

[28] “Dr. Gay is Recovering,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, October 23, 1932, and “Dr. Gay Resumes Practice,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, November 8, 1932.

[29] “Both doctors and Medicines Free,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, October 21, 1903.

[30] “Sarah Wiley Memorial,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, February 4, 1904.

[31] War Bond advertisement, Richmond Times-Dispatch, March 11, 1918.

[32] E.g., “Contributions to 100 Neediest Families Fun Thus Far Enough to Care for Less Than Half,” Richmond News Leader, December 14, 1951.

[33] “List of Candidates in Great Auto Contest,” The Virginian, March 20, 1913; “William T. Davis is Winner of Box for Getting Devil,” Richmond News Leader, June 12, 1913; “Believe it or Not,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, June 5, 1929; “Yarns come in Avalanche for Funny Story Contest,” Richmond News Leader, June 25, 1929.

[34] James Taylor Robertson, “Rod and Reel,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, November 27, 1936.

[35] R. L. C. Barret, “Ramblin,” Richmond News Leader, January 19, 1938.

[36] George Gay, “Declares Richmond Had Precocious Student,” Richmond News Leader, September 24, 1929.

[37] “Appreciative Writer Tells of Family Physician,” Richmond News Leader, October 2, 1929.

[38] George Gay, “The Voice of the People: A Physician Testifies,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, April 23, 1932. “Anent,” even at the time, was an old-fashioned word meaning “in regard to.” Gay may have been putting on a few airs by using it.

[39] “Church Hill News,” Richmond News Leader, February 11, 1910.

[40] “Real Estate and Building News,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, May 19, 1912.

[41] “Gay, George W.,” U.S. Census, Richmond, Virginia, April 6, 1940; Will of George W. Gay, October 28, 1936 (recorded September 1, 1950), Will Book 56:155, Richmond, Virginia.

[42] “New Auto Registrations,” Richmond News Leader,” July 25, 1935.

[43] Personal communication, Dave Yancey, Auburn, California,

[44] “J. C. Powers Succumbs Unexpectedly,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, October 1944.

[45] “Gay, George W.,” U.S. Census, Richmond, Virginia, April 6, 1940; Will of George W. Gay, October 28, 1936 (recorded September 1, 1950), Will Book 56:155, Richmond, Virginia.

[46] “Gay, Geo W. Jr.,” U.S. Census, Richmond, Virginia, April 15, 1950.

[47] Richmond and Fredericksburg city directories, 1915-1955, and Genevieve Nance Bootwright, Commonwealth of Virginia Certificate of Death, January 31, 1968.

[48] “Cousins, Violette P.,” U.S. Census, Richmond, Virginia, April 17, 1950.

[49] “$330,480 Left by Dr Gay, Will Reveals,” Richmond News Leader, September 1, 1950; “Dr George W. Gay Leaves Estate of $330,480,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, September 2, 1950; will of George W. Gay, Jr., October 28, 1936 (probated September 1, 1950).

[50] Historic Guns on Exhibit in Bank Here,” Richmond News Leader, January 5, 1951.

[51] “For Sale: Antique Gun Collection,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, March 11, 1951.