and Performance in Richmond, Virginia, 1908-1962

last revised: April 27, 2025

While it is unknown how Richmond compares to other American cities in regards to the richness of live African-American performance from about 1908 to 1962, it is hard to believe that many others of its size brought as many performances to as many theaters and tent shows as were present in this southern city during that era. Richmond’s position as a railway hub to many other cities in the South facilitated travel through the city and made it an attractive stop-off for traveling performers, and its large African-American population meant there would always be a ready audience. In the early days — the age of vaudeville — radio, television, and social media were, of course, unavailable for entertainment. At the same time, with only some exceptions, African-American Richmonders were not permitted to attend otherwise-White theater performances — and even then, could sit only in segregated gallery spaces that were so expensive that only the elite could afford them. In those theaters, African Americans saw White performers acting in shows written by White playwrights for White audiences. Black theaters were the first to give non-elite Black Richmonders a chance to see some of the finest African-American performers touring the country at the time.

Following is a list and descriptions of Richmond theaters that existed from 1908 to 1962 that presented African-American performers to African-American patrons. Many of these theaters were owned by Whites, a common occurrence across the country, so calling them “African-American Theaters” is acknowledged as a bit misleading. More information about two of these theaters, the Dixie and Hippodrome, is provided in the book, Nickelodeons and Black Vaudeville: The Forgotten Story of Amanda Thorp (Kathi Clark Wong, 2023), but this page is an attempt to show the entire depth and breadth of African-American Theaters and Performance in Richmond through 1962. On another page in this website (click here) is a 37-page table listing the performers who appeared at the following theaters. A few of the performers listed in the table were Richmonders trying to make a living in the entertainment business; they are identified as being from Richmond when that information was available.

A list at the bottom of this page provides the sources and abbreviations for the sources of information used. The website author welcomes additions and corrections to this information. Please contact her through the contact form.

Richmond, Virginia, Venues for African-American Theater-Goers:

- Ideal Theater. Located at 700 West Broad at the intersection of Munford (Munford is a parallel side street to Belvidere) (REJ, June 15, 1908). It was a store-front theater. Announced at its opening as a “colored” theater on June 11, 1908, it was owned by Joseph and H. T. Rainey who were White (REJ, June 11, 1908, and August 1, 1908, and Richmond City Directory, 1909, p. 869). Charles “Chicken” Jones, an African-American comedian of some renown, was one of a few early vaudevillians who played the Ideal (REJ, June 23, 1908, June 27, 1908, and July 28, 1908). Whites also attended the vaudeville performances there (REJ, June 15, 1908, and REJ, June 23, 1908). No other mention of this theater is found after August 28, 1908, when a city alderman who owned an undertaker’s establishment across the street made a noise complaint about it (REJ, August 28, 1908). The size of the theater is unknown; it was likely a former saloon or small shop with a cloth “screen” and projector set up inside where it would also show the short, silent films of the day. The building at the location of the now non-existent Ideal Theater today houses students for Virginia Commonwealth University.

- Globe Theater. Located in the former North Side Skating Rink at 1005-1007 Charity (First and Charity). Charles Moseley, an African American, leased the rink by March 23, 1907, and was using it as a rink but also was showing films and putting on dances, vaudeville shows, etc. (IF, March 23, 1907). Moseley renovated the space and opened it as a “theater,” but likely with removable, kitchen-table-like chairs and benches, by August 28, 1908 (IF August 23, 1908), and likely initially showed the short, silent films of the day. The first known vaudeville act at the Globe was the Whitney Stock Company (NYA, May 6, 1909), a big name in early vaudeville. The size of Moseley’s theater enabled him to bring in comparatively large acts with comparatively large musical groups to accompany them. Another important act brought to the Globe was the Black Pattie Company (NYA, February 10, 1910). The Globe closed in late 1910 after the White owners sold the building. Moseley sometimes exaggerated how many people the theater could seat, but it was probably around 1,000-1,200 people. The location of the Globe Theater today is an empty lot near Gilpin Court.

- Orient/Pekin Theater. 300 West Broad. The space was opened sometime by Charles Moseley (IF, September 17, 1910) after about September 1908 (RTD, May 5, 1908, and August 15, 1908) and was originally called the Orient (RTD, January 3, 1909). It probably originally showed films interspersed with some vaudeville acts. By December 1909, it had been renamed the Pekin (still under Moseley ownership) (IF, December 25, 1909). It likely was a bona fide theater with bolted-down seats (see the Dixie Theater below). Well-known acts brought to the theater included Walter Manigault and Tim and Hester Moore. The Orient/Pekin likely could seat around 150 patrons. The last known show at the Pekin was in late 1912 (IF, October 12, 1912). The building today is a pediatric dentistry practice.

- Dixie Theater. 18 West Broad (corner of Brook and Broad). The Dixie was a bona fide theater with bolted-down seats and other amenities conforming to the newly-enforced fire code. Opened as a White theater showing films possibly interspersed with some White vaudeville acts in May 1908, the Dixie was converted, likely in late 1909, to a Black theater, still showing films but likely interspersed with Black vaudeville. The owner was Amanda E. Thorp (White), and it was later managed by Walter J. Coulter (White). At the time the Dixie was converted to a Black theater, it could probably seat around 150 patrons. Thorp eventually expanded the seating capacity of the theater to about 250 patrons. By 1912, Black vaudeville acts likely had become more common at the Dixie than films at the theater. Thorp sold the theater to Charles Somma (White) in early 1915 who kept it as a Black theater, showing Black vaudeville often, if not nearly exclusively, until about 1921 when the Dixie was closed. (Walter Coulter and Charles Somma are known today as the developers of the Byrd Theatre.) Through most of its life as a Black vaudeville theater, the Dixie was associated with the Dudley Circuit, an early theater organization out of Washington, D.C., that sent performers on a “circuit” of theaters to perform; in this way, the Dixie received much high-quality and well-known talent. These included: Johnny Woods, the Griffin Sisters, Perry Bradford, Alberta Whitman, King and Gee, String Beans, and many others. (All information on the Dixie is taken from Wong, 2023, Chapter 3). Today’s building is an art and gift shop called the Sideshow Gallery, which has been restored by a recent owner, Jennifer Raines.

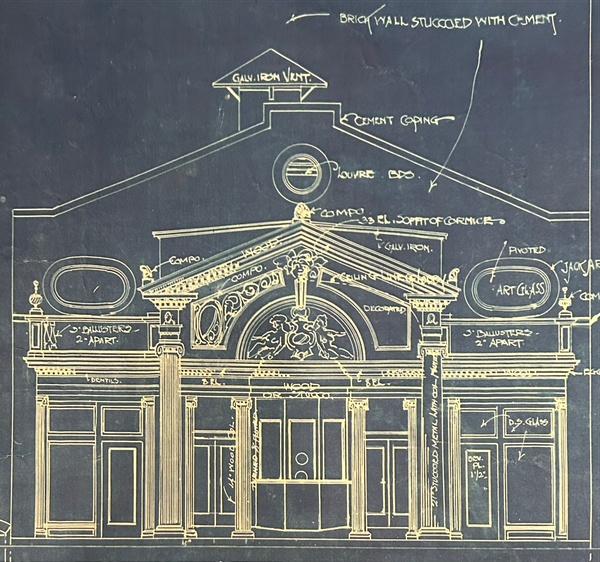

- Hippodrome Theater. 528 North Second Street, Jackson Ward. Amanda Thorp designed and built this theater which opened in March 1913. It was the first permanent venue built expressly for Black entertainment in Richmond. It could seat about 750 patrons. Thorp sold it to Somma in about February 1915, and he continued showcasing Black vaudeville for African-American patrons (Wong, 2023, Chapter 5). Like the Dixie, the Hippodrome benefited from its association with the Dudley Circuit to bring in many high-quality and important vaudeville acts. The Hippodrome was the major venue for live theater for African Americans in Richmond, occasionally also showing films, until about the mid-1920s when it turned more to showing movies after “talkie” technology became more common. News coverage about Richmond African American theaters waned in the 1930s, but there is occasional evidence that some live acts were still being hosted at the Hippodrome during that decade despite the effects of the Great Depression. Even less is known about the decade of the 1940s at the Hippodrome; that era is complicated by the effects of World War II as well as a fire that destroyed the original Hippodrome in 1945 (it was out of business for about a year). During the 1950s, the newly-rebuilt Hippodrome with its signature art deco architectural flare, became an important stop for R&B, blues, jazz, and later rock and roll performers, many of them very well known: they included the Ray-o-vacs, B. B. King, The Five Keys, Dizzy Gillespie and his Orchestra, the Orioles, the Moonglows, the Cadillacs, and the Ink Spots, to name just a few. Comedians also performed there, notably Moms Mabley and Pigmeat Markham (the latter credited with recording the first “rap” record). The theater began to decline after about 1962 and even lay vacant for some years. The building was restored in the early years of the 2000s by Ron Stallings, and today is an event venue. The Hippodrome is the only historic Black theater in Richmond that once hosted performances and still operates today as a business under its original name and in a building that is still largely intact as a theater. (All information is taken from Nickelodeons and Black Vaudeville: The Forgotten Story of Amanda Thorp [Kathi Clark Wong, 2023] or further research by Clark Wong from local and national newspapers. For more information, contact her through the contact form on this website.)

- Alexander Tolliver’s Big Show/Smart Set. Various Jackson Ward locations or nearby. Though Richmond’s tent shows were not technically theaters, they brought in over a hundred Black performers in each of multiple performances and in exceptionally large venues from 1915-1916. The most successful of these tent shows were those put on by Alexander Tolliver, a former traveling vaudevillian who, perhaps not coincidentally, was a native Richmonder. During 1915-1916, he brought three tent shows to Richmond: from June 28 to July 17, 1915; from September 26 to October 9, 1915; and from August 7 to early September 1916. The locations of the tents differed. The early 1915 tent was put up in two separate locations, running a week or so at one before moving to the other. The locations were 30th Street between Q and R streets (very near today’s Robinson Theater) and Brook Road and Mitchell Street (today near the I-95 intersection with North Belvidere Street). The late 1915 and 1916 tent shows were put up at Brook Avenue and Mitchell Streets. The canvas tents were massive, akin to those of circus tents, and could seat up to 3,000 people with another 300 standing, although one source said the tent could accommodate 5,000 people. “Ma” Rainey was among the featured performers, but there were many others well-known at the time. (Primary sources: IF, August 7, 1916, August 19, 1916, August 26, 1916, September 2, 1916, September 9, 1916, and September 16, 1916; and RP, June 26, 1915, and August 12, 1916. Secondary source: Abbott and Seroff 2012 [see Tolliver entries in index for page numbers]).

- Rayo/Howard/Rayo Theater. On Second Street, Jackson Ward. The Rayo Theater on Second Street between Marshall and Clay, about a block down from the Hippodrome but on the opposite side of the street, opened for Black patrons in the summer of 1921, likely showed films in what appears to have been a converted skating rink. It closed shortly afterward but made another go of it beginning in around April 1922, likely mostly showing films but also hosting events (including a major show featuring New York African-American fashions, meetings of a national African-American women’s convention, performances of local African-American drama and orchestra companies, etc.). The name was changed to the Howard for a time in 1923, a confusing name because of the famed Black theater of the same name in Washington, D.C. It closed again in 1923, re-opened in 1924, and rebranded itself once again as the Rayo when it brought in some at least middling names for the era, accompanied by elaborate and expensive marketing schemes. It filled the space for live performances for Black Richmonders in the 1920s as the Hippodrome switched to showing the new “talkie” movies. The Rayo closed permanently in 1925. The theater could seat about 1,000 patrons. Ownership of the Rayo/Howard/Rayo is not easily sorted out, but at least occasionally during its existence, Somma had significant financial interests in the theater. Today, the building is no longer there; the parcel is a parking lot. (All information is based on research by Kathi Clark Wong and comes from local and national newspapers. For more information, contact her through the contact form on this website.)

- (Robinson Theater. 2903 Q Street in Church Hill. This theater, built in 1937 for Black residents in this area of Richmond, was built to show movies rather than live performances, and so its history is not highlighted here. If it hosted performances, they were likely local. More information on this theater can be found here: National Park Service, Case Study on the Robinson Theater.)

- (The Richmond Times-Dispatch reported in a short article dated September 7, 1907, on a “colored vaudeville” venue located at the corner of Second and Duval streets. Its existence is only known because of this news article that reported the arrest of P. H. Ford, an African-American who was the apparent owner, for “erratic behavior.” The article also mentioned that the “theater” had a motion picture machine. Ford is probably Patrick H. Ford, a shoemaker, who was likely showing films as a money-making venture; it was probably located in a saloon at 800 N. 2nd owned by H. F. Thomas, a White man. The article notes that Ford was committed to jail in Richmond on a warrant for an examination before a “commission of lunacy” and that Ford’s relatives in Greensburg, Pennsylvania, would be contacted. No other mention of Ford or this venue as a “theater” can be located, and it probably was very short-lived, perhaps only a day or two.) (Source for information about Ford and the building at the corner of Second and Duval is the 1907 City Directory.)

Sources:

Newspapers

- Indianapolis Freeman (IF), Indianapolis, Indiana

- New York Age (NYA), New York, New York

- Richmond Evening Journal (REJ), Richmond, Virginia

- Richmond Planet (RP), Richmond, Virginia

- Richmond Times-Dispatch (RTD), Richmond, Virginia

Books

- Seroff, Doug, and Abbott, Lynn. Ragged But Right: Black Traveling Shows, “Coon Songs,” and the Dark Pathway to Blues and Jazz. University Press of Mississippi, 2009.

- Wong, Kathi Clark. Nickelodeons and Black Vaudeville: The Forgotten Story of Amanda Thorp. University of Tennessee Press, 2023.